Adult Stem Cells May Have Smarts To Guard Against Cancer, Stanford Researchers Find

The findings, from the lab of Thomas Rando, MD, PhD, associate professor of neurology and neurological sciences, suggest stem cells are careful when they undergo cell division so that random mutations in their chromosomes are not passed on to the next generation of stem cells. The results support a much-debated hypothesis proposed in 1975 by Oxford University geneticist John Cairns, PhD. Although other groups have uncovered hints that Cairns was right, Rando’s findings are the most detailed to date.

The results are published in the April 17 issue of the Public Library of Science-Biology.

Rando said no other work he’s done has created as much excitement among his colleagues in the stem cell field. “The lesson from this is that when something seems strange, don’t ignore it. Sometimes what puzzles you turns out to be the most interesting,” he said.

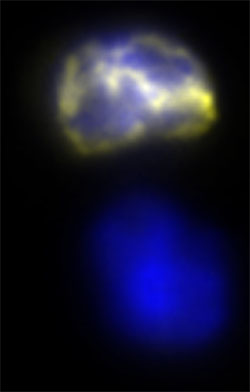

The image shows the two daughter cells of a muscle stem cell after it divides. The lower cell in blue remains a stem cell. The top cell has inherited the new—and possibly error-prone chromosome copy—and goes on to become an adult cell.

The idea that led to what Cairns called the “immortal strand hypothesis” was this: Stem cells found in adult tissues, such as muscles, brain or bone marrow, survive the lifetime of an animal, dividing when needed to replace cells lost to the ravages of bodily wear and tear. Every time that cell divides, it produces one offspring that becomes the new stem cell and one shorter-lived cell that replaces the body’s tissues. In order to split one cell into two, the original must essentially photocopy its genome and then divvy up material so that each cell gets one of every chromosome. Each round of photocopying introduces new genetic errors, some of which could derail essential functions and drive the cell toward cancer.

The mystery has been that stem cells don’t morph into cancer nearly as often as one would assume, given the number of accumulating mutations. Cairns suggested that adult stem cells might avoid cancer by shuffling off the newly created, error-ridden chromosome to the offspring that becomes an adult body cell. That keeps the pristine original chromosomes for the long-lived stem cell. A few mutations here or there won’t matter much to the new adult body cell, whose short lifespan likely won’t allow for the slow transformation into cancer.

When first proposed more than 30 years ago, Cairns’ theory led to some skepticism. Many scientists doubted that a cell could control which chromosomes go where in the random sorting that takes place when cells divide. The assumption was that as long as each cell got one copy of all 46 chromosomes, nature had done its job. In the normal course of things, both cells would end up with some originals and some photocopies.

Although some support for Cairns’ hypothesis surfaced over the years, it was never convincing enough to end the debate. Then Michael Conboy, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in Rando’s lab, found a troubling artifact in an experiment—over, and over, and over. The only explanation for months of aggravatingly strange results was that stem cells exert some control over which chromosome copy they retain.

“We did all sorts of experiments to figure out how this could have happened and this was the only explanation that fit,” Rando said.

The group had been studying at what point, after a muscle gets damaged, the muscle stem cells divide to renew themselves. Is it immediately after the injury, or days later? To test that, they developed a way of essentially inserting a different color paper in the cell’s “photocopier’’ each day after the muscle injury. Based on the color of the photocopied chromosomes, they’d know what day the cell divided. The original chromosomes remained uncolored.

What Conboy had counted on when devising his experiments is that after each round of division, both offspring cells would inherit some original, uncolored chromosomes and some chromosomes glowing brightly in the color of the day. That’s not what happened, even after months of painstakingly repeated experiments. The offspring stem cell’s chromosomes remained stubbornly uncolored. Carrying out a similar set of experiments using the normal muscle cells rather than stem cell, those cells behaved exactly as expected, incorporating the colored chromosomes into both newly formed cells. It was only the stem cells that were proving uncooperative.

“We kept thinking, this must be wrong, maybe we added the labels wrong,” Rando said. Eventually they realized that the only logical explanation was that the offspring stem cells eschewed any copied chromosomes in favor of the error-free originals, exactly as Cairns proposed. Once they finally accepted this explanation, they devised experiments to specifically look for proof of Cairn’s hypothesis. Those results are what the group published in the PLoS-Biology paper.

Rando said the next step is to figure out how the stem cells go about sorting chromosomes during cell division, determining which ones are older and thus unlikely to have mutations and which are new. For now, that’s as much of a mystery as it was when Cairns first published his hypothesis.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under an NIH Director’s Pioneer Award.